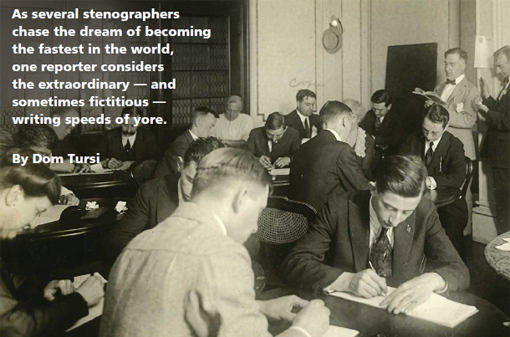

When I hear talk about amazing shorthand speeds, it always stirs my professional passions. The ambitious goal of 400 wpm is now on the horizon as the speed zenith of 2013. This has rekindled memories of speed contest thrills and evoked a desire to share my historical shorthand knowledge as director of the Gallery of Shorthand. There has always been fascination with man’s ability to write faster than most can speak. Noted fourth century Roman poet Decimus Magnus Ausonius, astonished by the skill of his amanuensis, felt compelled to comment, “I wish I could think as rapidly as you write… How is it that what my mouth has not yet expressed has already arrived at your ears?”

Contests of shorthand speed are of ancient origin. Try to imagine a group of toga-wearing scribes, furiously scratching crude forms on wax tablets. This is not fiction — it is historically accurate! The Romans’ insatiable appetite for competitions of all kinds included shorthand competitions, and Titus Caesar (Titus Fabius Sabinus Vespasianus, 11th of the 12 Caesars), loved to compete. (Is it surprising that he was always victorious?) This was the first known quest for shorthand speed supremacy. It is also the last such recorded period before the passage of 17 centuries.

IN ENGLISH, PLEASE

I consider the rebirth of shorthand contests to be the year 1720 in London, England. We are about to witness a battle between zealous combatants. But this challenge is not to be fought with swords. This is an attempt to determine speed superiority between shorthand inventors Dr. John Byrom (“Universal English Shorthand”) and James Weston (“Shorthand Completed.”) The weapons are quills — pens made from bird feathers. More in the nature of a private duel, this disputation was settled when Dr. Byrom was declared the victor with a speed of 250 words per minute.

The world’s third speed contest took place nearly two centuries later, triggered by an article written about the second. Shorthand writers of the time were given to overstatement and claimed speeds of 400 wpm, even 500 wpm, were not uncommon — although in fact they only resulted from vivid imaginations. At the 1886 Annual Meeting of the New York State Steno Association (later the New York State Court Reporters Association), a paper entitled “Stenographic Braggarts” debunked such assertions. So profound was this writing that it influenced court reporter A.B. Little of Rochester, N.Y., to offer a gold medal valued at $50 to anyone who could demonstrate the ability to write 250 wpm for five consecutive minutes, and convention discussion developed that no one present had ever seen anyone write even 225 wpm. No one accepted Little’s offer. But when Little reoffered it in 1887 (adding that it had to be read back without error), Isaac C. Dement, from Detroit, accepted the dare. He read it with 40 errors and therefore was awarded neither the coin nor the title of champion.

The stage was now set.

The first shorthand speed contest in modern times took place one year later, at the same association’s next convention. System inventor Andrew J. Graham offered a total of $500 in cash prizes to winners of a contest consisting of 5-minute readings at speeds of 250, 240, 230, and 225 wpm. Fred Irland wrote 1,308 words, netting 240.4 wpm after deductions by the grading system then in place. Dement’s 1,338 total words averaged 250.66 wpm. Seeking to encourage future contests, and with the consent of the participants, Graham divided the cash prizes equally and declared the contest a tie.

THE MODERN ERA

It is appropriate to pause at this juncture. Outrageous claims of extraordinary shorthand speed have been associated with shorthand seemingly forever. In 1919, 300 wpm for five minutes (99.9 percent) was proclaimed as the speed to beat, followed later the same year by announcement of a “New World’s Record” at 322 wpm. And there was the infamous claim, reported in the New York Times, of 350 wpm in 1922. (See the sidebar for a fact/fiction discussion.) Owing to the “absurd, ridiculous, and false” claims of shorthand speed made by “unscrupulous shorthand writers” of the time, a reliable, professional platform for the determination of shorthand speed excellence was necessary. These and earlier preposterous claims led the National Court Reporters Association to institute annual speed contests in 1909.

Most contemporary reporters likely are not aware that pen shorthand writers were every bit as fast and accurate as machine artisans. Their well-educated and cultured ranks worked in the same reporting arenas that exist today, provided daily and hourly transcript delivery and reached incredible records of speed and accuracy. Indeed, even when the NCRA annual speed contests commenced, the Pitmanic shorthand experts, who dominated the early contests over their Gregg counterparts, demonstrated the ability to write Q&A at 280 wpm — the same Q&A speed tested during the NCRA Speed Contests today.

Here are some remarkable feats of shorthand dominance.

Discussion of shorthand speed must begin with the distinguished Nathan Behrin. Considered the greatest Pitmanic writer of all time, this New York City and Long Island court reporter was the NCRA speed champion five times (1911, 1912, 1913, 1914, and 1922) and the only pen writer in the 1914 contest to defeat all machine writers — at 280 wpm.

The 1914 Speed Contest was remarkable because it was the first time that machine shorthand writers competed. The outstanding accomplishments of the nine teenagers trained on Ward Stone Ireland’s stenotype machine so shocked the pen-writer establishment that speed contests were discontinued for five years. Even when the contests resumed in 1922, stenotypists were not permitted to compete until 1952.

Here are some accomplishments following the 1922 resumption of the contests.

At the age of 18, New Jersey’s Charles Lee Swem became Woodrow Wilson’s campaign stenographer and then his White House stenographer for both presidential terms. Swem was the NCRA speed champion in 1923 and 1924 and the first Gregg practitioner to win.

In 1921, at the age of 15, Martin J. Dupraw entered his first NCRA speed contest — the only high school student ever to so compete. Four years later he became NCRA speed champion, defeating all seasoned speed writers of the day, including shorthand greats Behrin and Swem, with an “astonishing record for accuracy, making but three errors in transcribing 3,444 words.” As a result of Dupraw’s record-setting performance on the 1925 contest, speeds were raised 20 wpm on the literary and jury charge readings of the 1926 contest — which he then won with a stupendous eight total errors! Dupraw was also the speed champion in New York (1924, 1925, 1926) and Ohio (1926), and he set an Ohio accuracy record of one error on all three takes. For good measure he also won the 1927 NCRA contest.

BRING ON THE MACHINES

Following Arnold Cohen’s 1952 contest victory, he and twin brother, Bill, tied in 1953 with the same number of errors (although different) on each take: three on the Literary, four on the Charge, and two on the Q&A.

In 1958 and again in 1960, Nathaniel Weiss followed their sixyear reign by duplicating Dupraw’s 1926 record-setting feat of eight total errors (99.789 percent).

As if to say that no accuracy percentage should ever go unchallenged, J. Edward Varallo’s 1975 contest papers achieved a new accuracy level — six total errors (99.82).

And then in 1994 — as if to speak simultaneously to Marty Dupraw’s 1925 and Ed Varallo’s 1975 records, Candace Braksick’s contest papers resulted in the fewest total errors to date: three (99.91 percent).

Along the way we have seen perfect papers at contest speeds on the 220 Literary (Diane Kraynack, Mark Kislingbury), 230 Legal Opinion (Chuck Boyer), and 280 Q&A (J. Edward Varallo, Dom Tursi, Dale Varallo, Candace Braksick). The fastest shorthand speeds conducted under the auspices of noted organizations are 300 wpm for 5 minutes (Dom Tursi) and 360 wpm for one minute (Mark Kislingbury).

A NEW RECORD?

This year we sit on the precipice of a new world’s record. Several writers will attempt to write four dictations, one minute each, at speeds of 370, 380, 390, and 400 wpm. In a society that still considers “shorthand” an antiquated art form, I wonder whether a successful performance can help convert our old-fashioned image into a modern one.

DUBIOUS CLAIMS OF SHORTHAND SPEED

Many fictional claims have been associated through the years with man’s attempt to demonstrate extraordinary shorthand speed. Let’s analyze some historically important exaggerations.

CLAIM

January 19, 1919

300 wpm for 5 minutes with 99.9% accuracy

Accomplished by Herman J. Stich

FACT

- The dictation was at not more than 250 wpm

- No others were allowed to compete

- More than 50 Q&As, neither read nor written, were inserted into the transcript

- The contest was dictated by Mr. Stich’s friend and the results telephoned to the newspapers by Mrs. Stich

CLAIM

December 1919

322 wpm – “New World’s Record”

FACT

- Actual dictation speed was about 270 wpm

- The dictation lasted two minutes

- Q&As, not dictated, were included in final word count

- Not conducted under the auspices of an organized body

- Event staged by several colleagues as a “sporting proposition”

CLAIM

1920

280 wpm “Handicap Contest”

Winner: Nathan Behrin

All contestants (except Mr. Behrin) were conceded a handicap based on best prior NCRA performance.

FACT

- Actual dictation speed was about 247 wpm

- The dictation lasted five (5) minutes

- Q&As, not dictated, were included in final word count

CLAIM

December 30, 1922

350 wpm – 2 errors

The New York Times article referenced a sprint contest at the annual convention of the New York State Shorthand Reporters Association: “New World’s Record for Shorthand Speed – Nathan Behrin Transcribed 350 Words in a Minute with Only Two Errors.”

FACT

- Actual dictation speed was about 280 wpm

- The dictation lasted two minutes

- Q&As, not dictated, were included in final word count

- Not conducted under the auspices of an organized body

- Conducted under “altered conditions” from normal testing standards; “misleading”

- One of a “new form” of “blue-sky” contests to be succeeded by speeds of 375 to 425 wpm and that “the sky be the limit”

ALSO

Ward Stone Ireland, while promoting his new stenotype device, infuriated the shorthand profession with declarations that his students could perform at 600 wpm. Although his students were victorious, such boasts antagonized the seasoned pen writers and galvanized them against the “renegade” machine writers. This largely influenced their excommunication from national speed contests for nearly 40 years.