Theresa (Tari) Kramer, RMR, CRR, CPE, an official court reporter from Charlotte, N.C., recently provided CART to a juror. She described the experience for the JCR Weekly.

JCR | How long have you been a court reporter?

TK |28 years.

JCR | Have you been the reporter for a juror before?

TK | Yes, one other time, but the juror did not make it into the jury box. This was my first time one made it all the way through the trial process.

JCR | How did you get this job?

TK | I obtained this assignment based on my skills, equipment, and experience and because our courthouse recognizes the benefit and convenience of utilizing a certified realtime reporter. The jury services office advertises CART as an ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) option for hearing-challenged prospective jurors. They refer to it as a “note taker.” We have two full-time realtime reporters, and I was assigned to cover the assignment. The juror had requested someone to provide note-taking services during their jury orientation and during all phases of the trial process.

JCR | How would you describe the experience? What were you doing, and how did you do it?

TK | This was such a rewarding experience. I can confidently say that it was the most rewarding week of my career. It’s one thing to be involved in the trial process on a daily basis, but it’s an entirely different and humbling experience to help one on one with someone who otherwise would not have been able to participate in the jury process.

Through this experience I have realized that there are some folks who fall within a gray zone of not being deaf and only somewhat hard of hearing, people who don’t need a full-time interpreter and function well on a daily basis without any assistance. My juror was not fully deaf, has not been diagnosed with any hearing deficit, and does not read lips or communicate through sign language. She was fully capable of communicating her thoughts, articulate with her words, and responded appropriately to attorneys during voir dire.

Her challenge, as relayed by her, came when people speak soft, there are other noises in the background, or when the speaker is not looking in her direction. The sound suddenly cuts in half, and she begins to panic. Knowing this challenge and realizing the importance of her role as a juror, she decided to ask for a note taker to fill in the gaps during these kinds of moments.

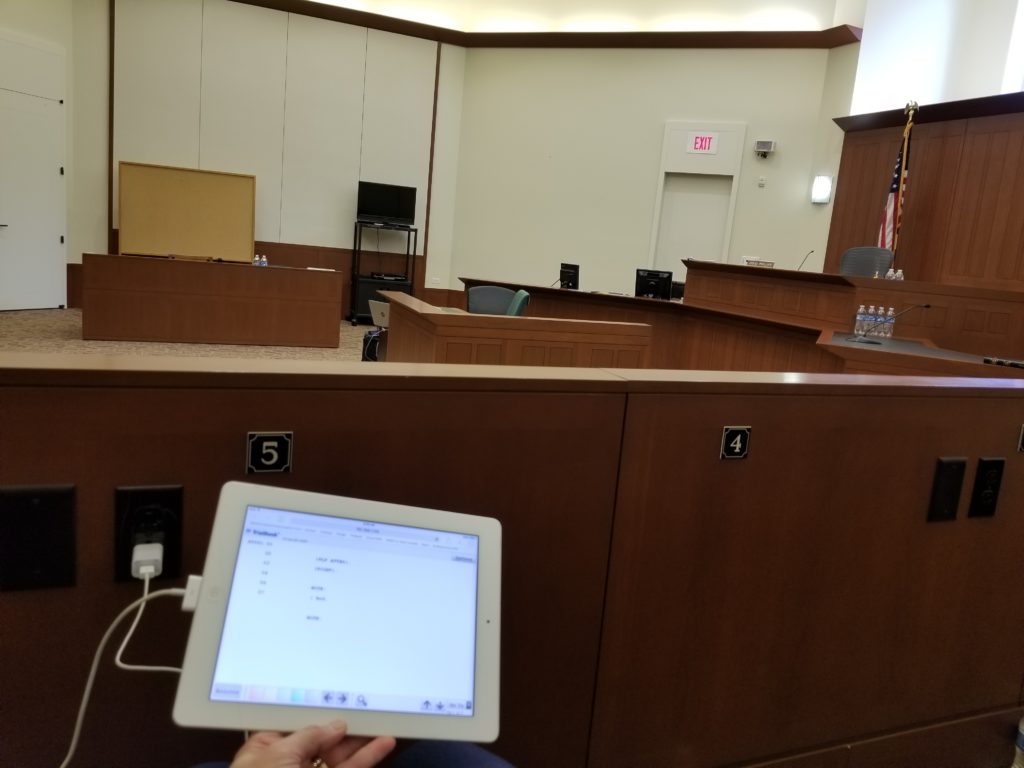

I met the juror at 8 a.m. on Monday morning in the jury assembly room. I discussed with her the services I would be providing, a little bit about the technology, and got some background on her hearing challenges. My employer provided me with a rolling cart, and I followed the juror wherever she was directed to go. She received my streaming feed through an iPad. I had two other iPads on a constant charge, ready to change out for the one she was using. I use a wireless router for the room only. While she was able to view the feed on the iPad, I noticed that my router would cut out when I moved the cart to another room. In the future, unless the juror is sitting in the jury box further away from me, I will just have them view the feed on my computer.

Eventually she was called into a courtroom and was put in the box on the first call by the clerk. I sat behind the official court reporter and provided a feed for her during the voir dire process. Shortly thereafter, she was approved and sworn in as a juror.

When the trial began, I was sworn in as an interpreter. Having this be a new experience for myself and the judge, I took the liberty of printing out some information from NCRA, the state of North Carolina’s policies on ADA requirements for trial participants, and a few other articles. I highlighted and tabbed the areas most pertinent to the situation and handed it to the judge. It was soon determined that I would act as an interpreter of sorts. My sole job during the trial was to meet her needs. When the jury went in and out of the courtroom, I was with her. I purposely did not stay in the courtroom during the parts of the trial when the jury was gone. I wanted to remove myself from any knowledge of the case and/or any impropriety.

She did express a desire to have me in the deliberation room because, when everyone was talking, she didn’t think she would be able to hear folks on the other side of the room. That moment came, and I got the enviable opportunity to be a fly on the wall during a jury’s deliberation process. I informed the jury of my role and that my iPad feed was just to be viewed by her, not to ask me any questions, and to treat me as if I was invisible in the room. I did, however, request that they “try” to speak one at a time. Any experienced reporter knows that this will not happen when you have 12 impassioned folks discussing an issue, but I felt I had to make the request anyway.

The deliberation takedown was fast and furious. One juror had been dismissed so it was a jury of 11 (civil case). In my mind, that was one less voice to pick up and write. I sat in the middle of the room. My client was to the left of me. Eventually we got into a rhythm. She heard what the people were saying to her left and next to her. I wrote mostly what I heard on the right side of me. I would not write what she said.

Logistically, I had literally five minutes to prepare for this, as the judge got the case to the jury rather quickly, so I had no time to prepare speaker IDs. As it turns out, I would not have had time to identify each speaker anyway due to the fast nature of the conversation. So what I ended up doing was adding two to three lines to my paragraphing stroke. When someone new spoke, I paragraphed and the screen went down a couple of lines. This provided space in between speakers. I know this was not the most ideal, but it’s what I had in the moment and it was my first time going through this experience.

On a side note, I am so very thankful for the NCRA CART group inside of Facebook that I feverishly made requests in that day. Several reporters chimed in on suggestions for deliberation takedown. I have such appreciation for my seasoned colleagues who have journeyed through this before me.

When the deliberations were finished, I had written 110 pages in one and a half hours. Mind you, this includes extra lines between speakers, but it was still extremely fast. What an exhilarating challenge that was! They threw the kitchen sink in, metaphorically, with the whole conversation. The terminology varied wildly — everything from religion to hematomas to DUI alcohol terms.

It was also interesting to observe the process. Eleven people who remained silent were suddenly full of thoughts and opinions, waiting impatiently to be the next one to voice their ideas. Most folks were boisterous while the minority were a bit reserved. In the end, however, they came to a consensus as a group because members were willing to compromise without relinquishing their principles. There was some heated conversation and one member who seemed to stand out from the rest on his opinions. This all reminded me of my bachelor’s classes in behavioral science. We studied things like this — what causes a group of people to respond and make a collective decision the way they do; how do outside influences, life experiences, and core beliefs affect a group decision? I was fascinated, like reading a book, to see this process unfold.

JCR | Did the juror say anything to you about her experience?

TK | Yes. At the end, I was in the jury room with the jurors and the judge. Everyone was speaking frankly and openly about the case and the experience. My client made it a point to thank me and the judge for allowing her to be an involved participant in the process. She said she had been very nervous about the experience (as are most prospective jurors) but especially because she had serious doubts about her ability to serve successfully. She said that my services made that possible for her. The judge also said he had never seen this technology being utilized before. He was familiar with realtime technology but not how it was used for a juror.

JCR | How long was the case?

TK | The juror entered the courtroom on a Monday afternoon, was sworn in at the end of voir dire, then came back the next two days for the trial. So it lasted about two and a half days.

JCR | Would you be interested in doing this again?

TK | I would definitely like to do this again. However, next time I would tweak my dictionary a bit to have more room sound definitions than I currently have; i.e., laughter, loud noise, private conversation held. I would also only bring my laptop into the jury room (thank you, NCRA Facebook group member suggestion). When someone recommended that, I metaphorically slapped my forehead like “oh, yes!” It would have made things go a lot faster had I just provided the juror with a view of my laptop instead of everyone waiting for my technology to reboot in a different room. But I don’t fault myself for any of this because it was all new terrain for me, professionally speaking, so I chalked it up to a wonderful learning experience.

While this appeared to have been a positive experience for the juror, it was eye-opening for me how beneficial court reporters are to the hearing-impaired community. There are folks like this juror who have no idea that this opportunity exists — people who do not fit the black-and-white description of a hearing-impaired client. I wish that CART was more readily known because so many people would find a genuine benefit from this technology. I would love to be involved in creating a CART-in-the-courtroom training program for our officials in North Carolina because, when preparing for and going through the juror’s time in our courthouse, I did not find much information on how to perform my role. It would have been nice to have a crash course of sorts or a cheat sheet to take with me throughout the assignment. We also need to update the verbiage in the interpreter oath, as it did not reflect my role during deliberations. All in all, though, I would definitely do this again because the experience far outweighed the challenges.