As the year draws to a close, we want to thank you for your help in celebrating 125 years of NCRA. Founded in 1899 as the National Shorthand Reporters Association, NCRA has evolved over the century-plus of its existence, and we have been delighted by the contributions of many to show the long history of shorthand and our members in the country.

One of the latest articles in this series included a look back at the Scopes Trial – and the reporters who worked the case. You can also review other ways we’ve celebrated this year on our 125th Anniversary page.

Finding Mrs. Maclaskey

By Linda Hershey

For decades I had been assigned to report civil cases in the Rhea County Courthouse located in Dayton, Tenn. During that time someone mentioned the Scopes “Monkey” Trial was held in that courtroom and there was even a tiny museum in the basement. But, being young, the world at that time revolved around me, and the only thing I could concentrate on was how cavernous the courtroom was, how incredibly hard the chairs were, and how hard it was to hear — especially when it got so hot they would open the windows with the train tracks just a block away.

Sheila Wilson, a coworker and friend, asked me to present a seminar for the Tennessee Court Reporters Association (TCRA). In it I talked about the history of some prominent court reporters of TCRA and three famous cases held in Tennessee. Naturally, one of those cases was the Scopes “Monkey” Trial. I wanted to find out about the court reporter who worked to provide the transcript — who knew there would be five?

As any good historian/researcher would do, I started by investigating the trial itself. Encyclopedia Britannica listed the Scopes trial as No. 5 in the top 10 important trials in history along with the trials of Socrates, Galileo, the Salem Witch Trials, and the O.J. Simpson Trial. I came to understand why: The Scopes Trial was the first time religion and science were debated in a courtroom.

But I wanted to figure out who had been the court reporters who provided daily copy and what the formatting looked like. After some time and effort, I was able to track down what was thought to be the original transcript.

In March of 1925 the Tennessee legislature passed the Butler Act which banned the teaching of evolution in all educational institutions throughout the state. The ACLU immediately put an ad in all Tennessee newspapers looking for a teacher who would be willing to test the new law.

The economy of Rhea County relied on two basic industries at that time: Growing strawberries and the Cumberland Coal and Iron Company. Because there had been a downturn in the economy in 1925, three men met at Robinson’s Drug Store in Dayton to discuss this opportunity to bring some publicity to the county. George Rappleyea, manager of the Cumberland Coal and Iron Company; Sue K. Hicks, a young local lawyer; and Walter White, superintendent of the Rhea County schools, presented their idea to John Scopes, who agreed to be the test case.

Scopes, 24 years old, had graduated from the University of Kentucky the year before with a major in law and a minor in geology. He had then relocated to Dayton where he became the Rhea County High School football coach and occasionally served as a substitute teacher. According to research, Scopes helped coach the students how and what to testify so that he could be arrested. Years later he confessed that he did not remember actually teaching evolution the day he had substituted for the science teacher.

The case took on national fame when Clarence Darrow agreed to represent Scopes and William Jennings Bryan agreed to be one of the prosecutors for the State of Tennessee. This set the stage for a tremendous amount of publicity. The courtroom was outfitted with the latest technology: Telegraph and telephone wiring, movie-newsreel camera platforms, and radio microphones were installed. WGN radio ended up broadcasting the trial live at a cost of more than $1,000 a day just for the telephone lines – $18,000 a day in today’s dollars. The full transcript was printed each day in the Chattanooga Times; more than 200 newspaper reporters from all parts of the United States and two from England came to Dayton; twenty-seven newspapers in China bought and published daily full telegraphic accounts of the trial, and two movie cameramen had their film flown out daily in a small plane.

Six blocks of Dayton’s main roads were transformed into a pedestrian mall, and a speaker’s platform was built on the lawn of the courthouse. During the trial the courtroom was so crowded and hot that the trial was moved outside. The town took on a circus-like atmosphere. Baltimore [Md.] Evening Sun columnist H.L. Mencken nicknamed Dayton “Monkey Town,” describing the streets jammed with Bible salesmen, souvenir hucksters, and a performing chimpanzee named Joe Mendi (who starred on Broadway, in vaudeville, and in motion pictures) playing a miniature piano.

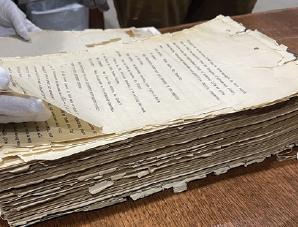

But I wanted to figure out who had been the court reporters who provided daily copy and what the formatting looked like. After some time and effort, I was able to track down what was thought to be the original transcript. It ended up being a copy of the transcript housed in the Rhea County Circuit Court Clerk’s office and was extremely fragile.

To learn about the five court reporters on this case, and to view the full text of this article, NCRA members can use their membership credentials to log into the November/December issue of the online JCR Magazine.

Linda Hershey, FAPR, RDR, CRR, CRC, is a broadcast and CART captioner from Chattanooga, Tenn. She can be reached at hershey915@gmail.com.