NCRA is a nonpartisan organization and does not choose sides on the political spectrum. NCRA works with both parties to advocate for court reporting and captioning issues. However, we wanted to give credit where credit is due: Kudos to the stenographers who captured the marathon speech on the floor of the Senate. This story is to celebrate the amazing skill set of the professionals who take down the history in Congress, regardless of the political party. We hope that you will read this in that light.

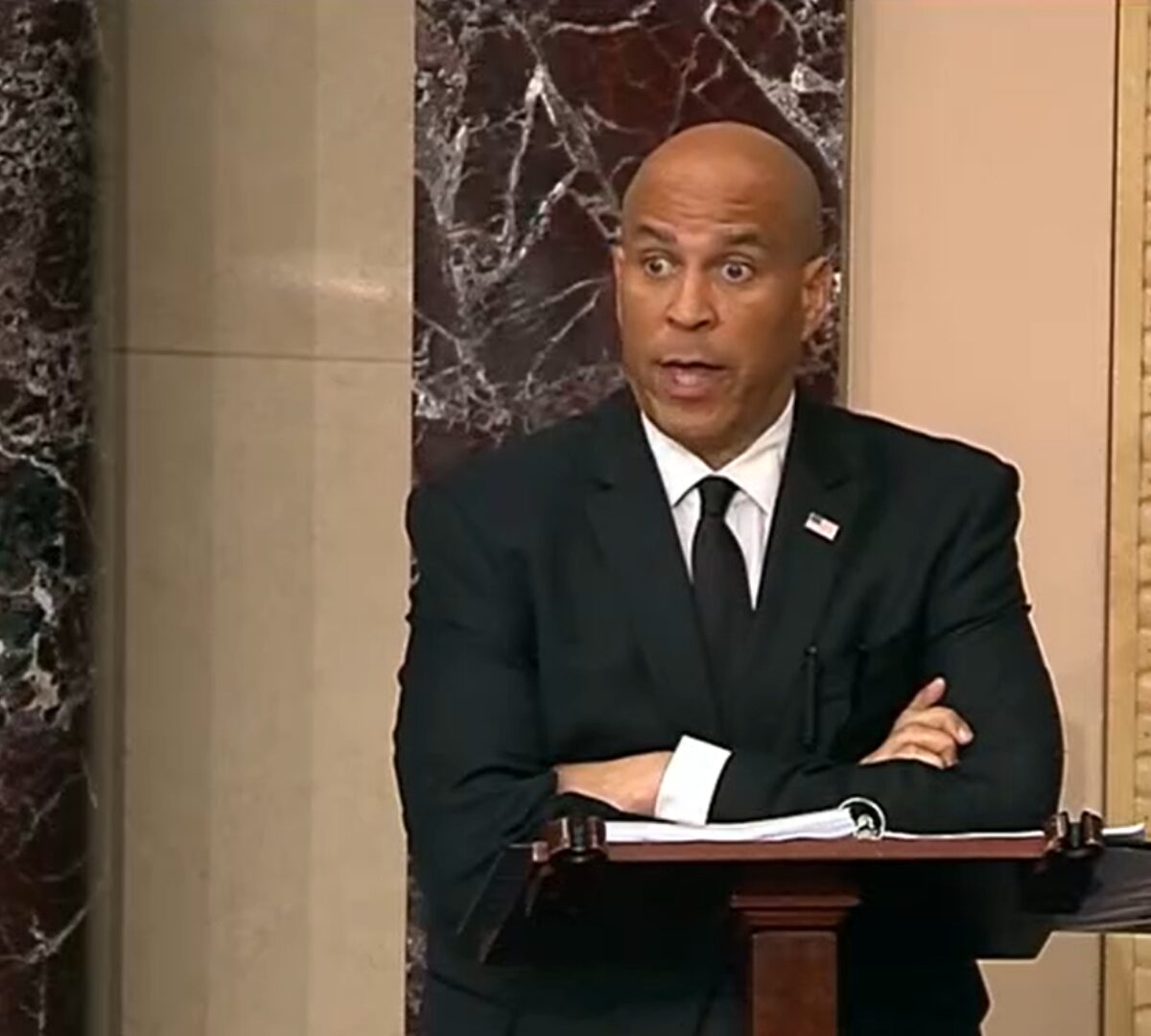

New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker stood on the floor of the U.S. Senate for 25 hours and four minutes delivering the longest speech in the history of the world’s most deliberative body. His remarks, intended to protest the second Trump administration and Senior Advisor Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency, shattered the previous record set by Sen. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, who filibustered the Civil Rights Act of 1957, a record that stood for 68 years. While technically not a filibuster, this marathon session tested not only the stamina of the senator — who played tight end while attending Stanford University — but also that of a dedicated team of stenographers. Writing away on their stenotype machines with quiet accuracy and integrity, the public servants ensured every word was preserved verbatim in the Congressional Record — a testament to their solemn duty as guardians of America’s legislative history.

For more than a century, Congressional stenographers have been the backbone for documenting the House and Senate: capturing floor remarks, motions, committee hearings, State of the Union addresses, and pivotal moments like declarations of war, treaty enactments, and impeachment trials. From the House’s formal adoption of stenography in 1873 to record proceedings in the Congressional Record to the Senate’s parallel tradition under the Secretary of the Senate, these civil servants have blended physical stamina, technical mastery, and an unwavering commitment to accuracy. Since 1899 the National Court Reporters Association (NCRA) has been proud to represent both current and former stenographers who have served in the U.S. House and Senate, though for this story — amid unprecedented times — we chose to interview a former official stenographer, Melinda Walker, RPR, CMRS, of San Saba, Texas, to respect the privacy of members currently on duty.

Walker shared insights into the grueling yet vital work of congressional stenographers. During Senator Booker’s speech, Senate stenographers worked in shifts, which are typically 15 to 30 minutes on routine days but can stretch longer during marathon sessions. Each reporter, armed with a stenotype machine, captured syllables phonetically in realtime, translating them instantly into English. “In the House we rotated too,” Walker explained. “A normal day meant going up for your turn, coming back down, editing, proofing, and repeating — gavel to gavel — until it’s published in the Congressional Record.” For filibusters or extended sessions, respite came in adjacent offices, where House stenographers once relied on reclining chairs with footrests to catch brief naps.

The contrast between a typical day and high-stakes events like the State of the Union is stark. “On State of the Union days, business wraps early for security sweeps,” Walker recalled. “Only one reporter is on the dais during the speech while others rotate downstairs, watching and preparing the Record. It’s almost ready by the time the president finishes.” Unlike the unpredictable flow of a filibuster, the State of the Union is a sprint with the rare, unanticipated stumble — scripted yet demanding, flawless transcription under international scrutiny. During Booker’s speech Senate stenographers faced a different challenge: endurance. Standing alongside the Senator, they mirrored his resolve in addition to operating stenotype machines.

Stenography’s roots in Congress trace back to the 19th century. Before 1873, House proceedings were summarized by newspaper reporters. The Congressional Record changed that, and by 1913 court reporters and congressional stenographers alike embraced cutting-edge technology in the stenotype machine, revolutionizing the process of capturing the spoken word. Today stenographers in both chambers continue that tradition of service, transcribing not just speeches, but also committee markups and providing closed captioning for the deaf and hard of hearing, a service that amplified Booker’s address to a wider audience.

While many Americans presume C-SPAN is the official recordkeeper of Congress, the camera was introduced to Congress for the first time in 1979 by a young Congressman from Tennessee, Al Gore. “Even though something’s said on the floor, it doesn’t automatically go into the Record as-is,” Walker said. “Parliamentary procedure must be applied, and we handle that.” Digital systems falter where human skill excels. Background noise, overlapping voices, and poor audio quality leave gaps marked “inaudible.” Stenographers, present in the room, discern speakers and intent on the fly, delivering a trusted, impeccable product. Trained to handle speeds exceeding 225 words per minute, they rarely stumble, though audio backups do serve as a last resort when chaos reigns.

While reports have brought to light the White House failing to accommodate their own stenographers in the current and previous administrations, lapses of documentation for both public and private remarks of a president and their administration are a serious failure for transparency. Congress, however, remains steadfast in its reliance on stenographers. The House once employed 18 reporters for floor and in-committee work, though numbers have shifted in recent years. Senate figures are less clear but equally vital. Differences exist — House reporters sit, Senate reporters stand and roam, reflecting chamber layouts — but the mission is the same: to document the day-to-day governance of the United States from procedural votes to historic trials’ convictions and acquittals.

As Senator Booker yielded his time, the Senate chamber applauded, a rare deviation from the decorum expected from members, staff, and visitors alike.

The stenographers remained the only ones at their posts, listening intently as business resumed. Their work — often unseen, yet indispensable — ensures that every word from filibusters to peace treaties endures for posterity on the record.