By Leah Willersdorf

I had three life dreams when I was a young girl between the ages of 15-17. In no particular order, one was purely materialistic and achieved with my first paycheck for being a fully fledged stenographer back home in Australia. Another one was – well, only a handful know that one, so let’s just keep it that way (and I’ll just say that particular dream achievement is totally doable and should have been ticked off well before now). And the third one was, for anybody who knows me, to become a court reporter. It’s a natural progression that, through one dream becoming a reality, new dreams and goals will be born. And so this piece for the JCR Weekly is about one of those steno dreams.

Packing up my steno machine – yes, even those heavy ones circa the Steno-Lectric age – and throwing a week’s worth of clothes, shoes, and toiletries into a suitcase before boarding a plane has always been a part of court reporting for me, even when starting out in Adelaide, South Australia, and going to places like Mt. Gambia, Kangaroo Island, and Coober Pedy, among others. After Adelaide came being based in the UK for the past almost 26 years, which has continued my thirst and love affair for international reporting and travel, taking me to many of the major Continental cities of Europe – and some not so major – and as far afield as the Middle East, until now.

It was in mid-September 2020 that I was first asked if I would be interested, willing, and able to travel to Africa to cover a war crimes trial for the United Nations. The United Nations is the most powerful intergovernmental and international organization in the world, striving to maintain international peace and security and, quite simply, to see harmonization and peace-loving cooperation throughout the nations who ascribe to its 1945 charter. Thinking back now in January 2021, I remember reading this particular work offer over and over, but it didn’t take me long to respond with “Deffo!” I had been Facebook friends with Stacey Donison, RPR, CRR, for three-and-a-half years prior to her and I, along with the jovial Jason Meadors and hilarious Heidi Thomas, being asked to attend the 2019 Denver NCRA convention to be on a panel for international reporting called “Flying Fingers.” It was then that Stacey and I not only shared a few G&Ts and cemented a true friendship, but we also discussed possibly working together somehow in the future. And that time was now upon us!

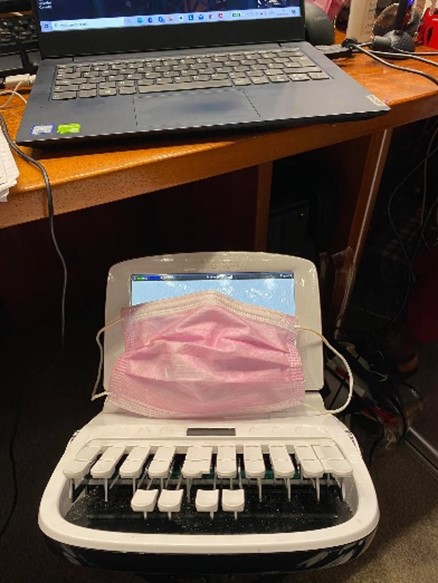

At the beginning of October, having had three-and-a-bit weeks to get organized; receive various injections; be COVID tested the day before flying (which entailed a four-hour round trip in the car); figure out logistics and equipment; all the while still working, invoicing, proofreading, emailing, more proofreading; waiting for new steno chargers to come in time (which they did, thanks to Stenograph!); making sure my home was in order and house-sitter ready; packing and having the kit spread across two big suitcases in case one didn’t turn up yet still having two fully functioning kits in my carry-on; the stress I put upon myself was up and down, in and out, and I think I shook it all about, too. I really did have to stop and take deep breaths. All manner of emotions were swimming around in my belly and brain, like the nerves and butterflies; like the what if I’m not actually up to the job; the oh, my goodness, it’s Africa!; the can I actually do this; the being away from home for so long; the I need to check my vaccinations; the I need to find a house-sitter; the what’s my mum going to say (yes, still); the X, the Y, the Z. Then I stopped. And I breathed. The day I left, I had 30 minutes to spare before my taxi arrived, so as I sat and sipped tea, tears rolled down my cheeks. I was overwhelmed, the tears being a welcome release, and it was time to believe that my dream was coming true. For real.

I arrived at Kilimanjaro International Airport, Tanzania, in the late evening where I was met by UN security personnel who drove me to where my new home for the foreseeable future was to be in Arusha. Upon waking the next morning, I opened my curtains and was faced with the most beautiful sight of Mt. Meru from my balcony. She is a dormant stratovolcano (second highest in Tanzania to Mt. Kilimanjaro) and is like the centrepiece of Arusha, overlooking almost anywhere you go in the city. It was at that moment that I felt a kind of abatement of my stresses. After all, I was there now and didn’t have the worry of all that goes with traveling, whether in a pandemic or not, including knowing that all your luggage has arrived with you. Now it was time to focus on the job at hand, something which I hadn’t even had time to think about really. After having another COVID test, which was to take up to six days for the result, I stayed in and around the hotel prepping for the trial – lots of reading and doing an abundance of dictionary work.

On day five, I received my negative test result and was now allowed onto the compound. We still had three working days before the opening statements and that was plenty of time to get set up in the courtroom, test out all the tech (this court is in the top five of the most state-of-the-art courtrooms in the world and certainly the best in the African region), become au fait with where everything is on the compound, and do even more prep. You can never do too much prep work for any assignment!

Two days before we had an in-court meeting with all the counsel and representatives of the different units and sections which make the compound run as efficiently as it does, I suffered from a bout of food poisoning which I couldn’t let beat me. My trusted driver, and now friend, Mr. Misoji, came to my rescue and for that I cannot thank him enough. At the in-court meeting – yes, which had to be taken down and a transcript prepared – each rep was invited to say a little bit about their roles and anything others can do to help in fulfilling those roles. I represented the stenography team, so I’m sure you can pretty much guess what I had to say: mics and headphones on are a must; try not to talk over others; remember the realtime transcript is not the final; explain the scopists’ roles; and I urged them not to follow my lead of speed-reading a document – I had four-and-a-bit pages of script to read out within five minutes!

A few days later, the steno dream became a reality. This, just a sign on the side of the road in the Kisongo area with arid earth around it, was pointing in the direction of where my dream would come true. I had passed it a few times before the big day, and I’d been up the hill a few days earlier. This day, though, was like no other. This day the road sign looked a little different, probably only to me, because it was pointing to where 1 kilometer away I was about to be on probably the biggest steno stage of my career so far. And maybe ever.

Feeling like the kid who, on the first day of secondary school, knew nobody because none of her fellow primary school girlies were going to the same school now, I stood and waited for my contractor pass to be made and activated, all the while nodding and smiling at passersby. Finally, it was done. I scanned my pass and the revolving security gate worked. It worked! The chick with a weird surname from a little suburb on the other side of the world stepped through the gate and into her dream reality.

I removed my disposable mask and simply stood there. My colleague, the French stenotypiste, had done this walk many times before and she queried why I stopped. I said, “Look at this. Just look.” And I truly do think she saw it all again herself for the very first time.

We waited for our escort (first day and all that jazz) who was to show us around everywhere before taking us into the courtroom itself. I took it all in, every little bit of it. Even now when I look back at the hundreds of photos I took throughout my entire time there, I feel like I’m doing it anew all over again.

The courtroom is not a large room by any stretch of the imagination, and it certainly isn’t made for a big, multi-handed trial, never mind the plexiglass jungle that it had obviously, and understandably, been turned into. With limits on the number of people each team could have in the courtroom at any one time due to COVID, the public gallery was now the dock and/or extra defense team tables. We stenographers are usually tapping away in front of the court officers and judges, but this time we were to be seated in the row behind the prosecution team. The courtroom is circular and, from the outside, resembles the Maasai huts in this area.

The Big Moment was getting closer and, as it did, counsel would come in and disappear again. I had prepped my butt off and so I knew who almost everyone was by face. The courtroom slowly filled like a church does for a wedding – thanks to a good friend for that analogy – and I began to feel excitedly sick and nervous. I’m used to wigs and gowns, so to see counsel in black robes and white jabots (aka neck doilies, court bibs) was nothing necessarily new. Just as the regalia was not new to me, neither were the three loud raps on the judge’s entrance to announce his imminent arrival. I heard the first and very quickly realised I was twisted up in my headphones and a couple of other cables. I had to stand and bow in about three seconds’ time but wasn’t sure if I’d get unraveled and be able to carry out such a maneuver with everything so higgledy-piggledy. The third rap came and somehow – not sure how because, well, it’s a blur – everything was tickety-boo, and I stood, bowed, then sat down with my fingers poised in the home position. And so it was that I took the opening statements in a United Nations war crimes trial. We continued on and finished the prosecution case at the end of November.

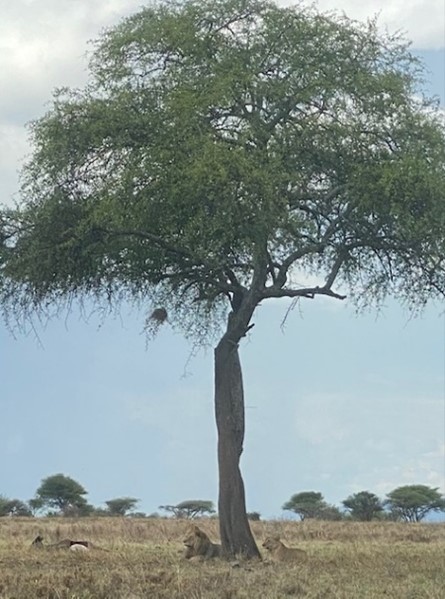

A benefit of any international assignment which is longer than two FIFO days (fly in, fly out) is that, if you’re lucky, you get to see the sights. For those of you wondering what I did during my downtime while in Africa, well, there’s only one thing to do: a safari, right? I was lucky enough to have a good number of weekends so I did do a fair bit of getting out and about, including going on two safaris, visiting a Maasai village and some of the markets, as well as mixing with the some of the locals.

Over the years, I’ve worked for a few UN organizations but this one has meant the most. Whilst the content can and will be harrowing, to say the least, in a war crimes trial, as a realtime stenographer, this kind of work is challenging in so many ways. I am honored to join the ranks of the stenographers from around the world (some of whom I have the pleasure of knowing) who over many, many years have reported the UN hearings, trials, and tribunals in what truly is a front-row seat to international justice and history.

All told, I spent 53 days away from home, saw some absolutely magnificent sights, and fulfilled a lifelong steno dream amid a worldwide pandemic. I sat and watched the locals (both the two- and four-legged kind) with the utmost respect, amazement, and gratitude for the circle of life; I saw extreme poverty up close and personal; made some wonderful friends; and am looking forward to going back to finish the trial. All of it has affected me, and in so many ways, but I am forever grateful for everything that goes along with being an international realtime stenographer. Will that almost-30-year thirst for international reporting ever be quenched? I highly, highly doubt it. Hakuna Matata.

Leah Willersdorf, RPR, CRR, is a freelance court reporter and captioner based in London. She can be reached at courtreporterlondon@gmail.com.